Adrian Newey’s Red Bull exit comes at a time when the dominant Formula 1 team has already been embroiled in huge off-track drama.

But all Newey’s departures from teams have been in seismic - and sometimes quite strange - circumstances.

They’ve all been explored by our Bring Back V10s classic F1 stories podcast series over the last four years - so for the full in-depth stories and our panellists’ memories of them, listen to the episodes in full on the embeds below.

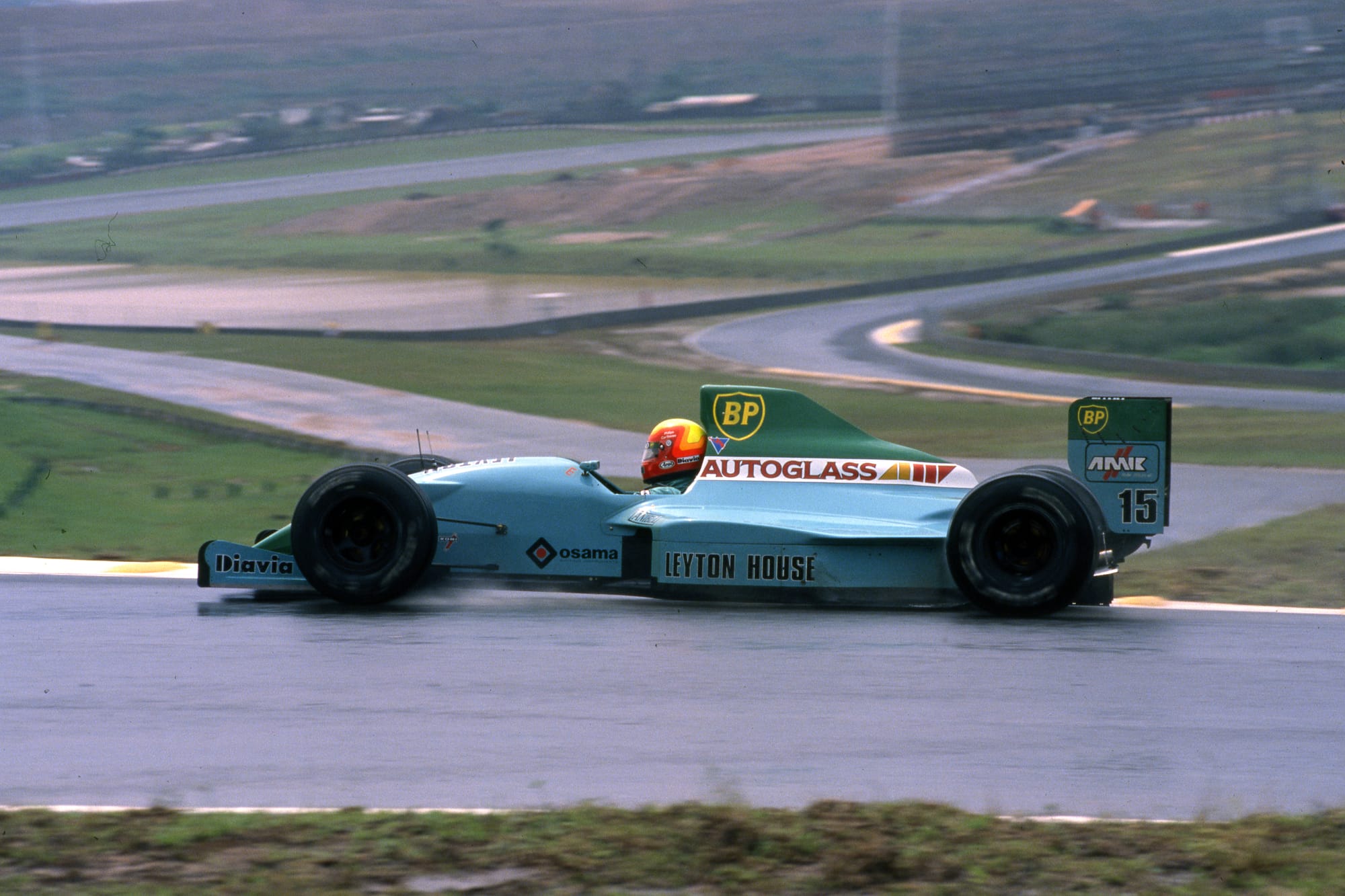

LEYTON HOUSE: EDGED OUT BY THE FINANCE GUY

“The team was obviously beginning to lose confidence in me. Maybe I was slipping, making mistakes. Maybe 1988 was my pinnacle and I was only capable of being a one-hit wonder.”

Adrian Newey’s summary - in his book How to Build a Car - of the self-doubt enveloping him as his Leyton House designs struggled through 1989 and early 1990 after sometimes hassling the ultra-dominant McLarens in 1988 is hugely at odds with everything that followed in his career.

But in the end Newey’s exit from the former March team happened just as its car spectacularly (if temporarily) improved.

Newey was aware the 1989 car had some fundamental problems and tried to make its successor what he called “a desensitised” version of it. But it was just as bad as what came before and Leyton House failed to qualify six times in the first six races of 1990, including a double DNQ in Mexico.

A dramatic disparity between the data from Leyton House’s usual windtunnel in Southampton and the new Comtec tunnel former team owner Robin Herd was setting up deepened that puzzlement - but also led to Newey discovering that the rolling road floor of the Southampton tunnel had bowed, meaning the car was sitting above a “gently concave” surface. As Newey put it: “this naturally unloaded the diffuser, leading us to develop a more aggressive shape that could not cope in reality”.

He went to work redesigning key parts of the car including the diffuser, although the Comtec tunnel also showed some aero separation underneath the front wing that hadn’t been detected in Southampton.

As Newey went through a cycle of redesigning parts, testing them, and making adjustments, there was another issue on the horizon.

Leyton House owner Akira Akagi was in financial trouble, so he brought in a new team financial director named Simon Keeble to - as Newey put it - “tighten the purse strings on his behalf”. And with team boss Ian Phillips recovering from meningitis, Keeble became acting team principal.

Keeble had doubts about Newey, perhaps understandably after a year and a half of underperformance. Newey says they “were at permanent loggerheads, getting into shouting matches”, and Keeble was making it quite clear he was approaching other designers.

Keeble doubted Newey’s claims about the diffuser, but eventually agreed to spend the money on the design work.

In the meantime, Newey was approached by Williams, which wanted him as head of research and development.

Newey accepted the offer, but before he had a chance to resign from Leyton House, he was - in his words - ‘effectively sacked’ when Keeble informed him the team was recruiting Chris Murphy from Lola as its new technical director and Newey could either leave or accept a lesser role within the team.

Keeble told Autosport during the French GP weekend that the factory was like “a morgue” after the double DNQ in Mexico, and the team was “in a really dire state”.

But things were very different by the time he gave that interview. Both Leyton Houses qualified in the top 10 at Paul Ricard as Newey’s new diffuser took effect and the team benefitted from a resurfaced track that played to the design’s strength on smooth circuits.

A bold no-stop strategy meant Ivan Capelli and Mauricio Gugelmin moved up to first and second just a fortnight after not even getting on the Mexico grid, and though Gugelmin retired with a blown engine, Capelli finished second behind Alain Prost’s Ferrari.

Keeble did credit Newey for the design changes that got Leyton House back on the pace, but also said Akagi “doesn’t understand why in 1988 we were on top of the world, and in 1989, when he buys the company, everything went wrong”.

Of Newey he added: “Adrian was very good at aerodynamics but Chris is more of an all-rounder and hopefully he will be able to put together a good team of people. Rather than just being known for one person, we want a team.”

Newey, who watched the race from his sofa, “took pride in the result and pleasure from proof that I’d resolved a problem that had come close to breaking my spirit”.

It left him thinking ‘what if?’ because he reckoned the performance of his upgrades would have given him the upper hand over Keeble politically.

But he pointed out the reason Keeble was there in the first place was because Akagi was in financial trouble. Akagi was eventually arrested in late 1991 over financial irregularities, and the team limped on under its old March identity for just one more year before folding.

WILLIAMS: SNUBBED OVER DRIVER CHOICES

Though hired as head of research and development, Newey was promoted to chief designer on his first day at Williams as Patrick Head had so much faith in his potential. Success quickly followed.

But cracks emerged just as quickly, with Newey unhappy with how Nigel Mansell was treated by Frank Williams and Head in the saga that led to him leaving F1 for IndyCar at the end of his title-winning 1992 season.

When Newey signed a contract extension in 1993, it included a clause saying he would be involved in major decisions including driver selection. In his next deal in 1995, a say on engine suppliers and in any battles with the FIA was added. “No more decisions made over lunch for me to learn about them much later,” Newey wrote.

There was also a pay rise, which was never Newey’s main motivation, but reflected the success he’d helped Williams achieve and came at a time when Ferrari and McLaren were showing an interest in him.

The ‘having a say’ agreement was soon shaken. Newey was on holiday when Williams tested Jacques Villeneuve in 1995, but had agreed with Williams and Head that the Indianapolis 500 winner needed to get within a second of the pace to earn another test.

Villeneuve got within half a second of Damon Hill, and without another test, or Newey being consulted, he was signed for 1996 to replace David Coulthard.

Newey reminded Williams on his return that his contract made it very clear he was supposed to be involved in those decisions. He didn’t take well to the initial response of “but you were on holiday…”, and Frank apologised, saying it was force of habit. Newey was assured it wouldn’t happen again.

Yet it did just months later, when Williams signed Heinz-Harald Frentzen to replace Hill for 1997 before the 1996 season had even begun, and Newey didn’t discover it until he quizzed Head when the story broke in August ‘96. Head confessed the bosses had been meaning to tell him. Newey was furious.

Things were made worse because Newey had moved back into a race engineering role in ’96, working with Hill following the departure of David Brown to McLaren with Coulthard. It was a repeat of the Mansell affair: Williams was booting out another British driver on the verge of winning the title.

Newey still doesn’t know why he wasn’t told about the Frentzen deal, but it was another clear example of Williams not honouring the terms of his contract.

He told Williams he wanted to leave, and when he was reminded he was under contract until 1999, he said that agreement had already been broken by Williams for not consulting with him on these big decisions. By now, Newey felt it was clear he’d be a fool to believe any further promises of “it won’t happen again”.

He later described Williams and Head as “creatures of habit who couldn’t adapt to a new order”, and that he understood “there wasn’t room for a third person at the table”.

Newey had an offer from McLaren, and Williams assumed his complaints about his contract not being honoured were just a ploy to get a pay rise. Frank Williams went above McLaren’s offer - without even telling Head. Newey declined it.

Legal proceedings loomed, although it never got that far as McLaren settled matters with Williams in advance. Having mellowed on the situation in the years since, Newey accepts today that it’s probably a good thing it didn’t turn into a fully-blown legal fight.

It had long been rumoured that what Newey really wanted out of Williams was a stake in the team. He has never spoken about that directly, although his comment about there being no room for a third person at the table could be interpreted along those lines.

In 2012 Frank Williams said Newey wanted shares in the team, and he accepted it was a mistake not to hand over a small percentage to give Newey the feeling he was truly a part of Williams.

McLAREN: THE TEAM HE LEFT TWICE

It didn’t take long for Newey’s McLarens to become F1’s benchmark and return the team to title glory. But it also didn’t take long for his relationship with Ron Dennis to sour - to the extent that he effectively left the team twice.

In August 2000 Dennis told Newey and Martin Whitmarsh that he eventually wanted them to take over the running of McLaren.

However, when Newey asked when that was likely to be, Ron said: “I’m not prepared to put a timescale on that. But look, I want your commitment. Are you prepared to do that or are you not?”

Newey says Whitmarsh pledged his loyalty, but Newey declined, saying: “I’m not going to give you my word that I’ll sit here indefinitely waiting for you to retire.”

Newey said a chill blew through the air during that conversation, and his relationship with Ron was never the same again.

Early the next year talks began over Newey’s next contract.

Newey said in his book that he went into the negotiations “with optimism” given McLaren’s performance under his watch.

So he was taken aback when Dennis offered him a pay cut for a new deal, and told him: “take it or leave it”.

“I’d had a pretty substantial joining fee at McLaren, plus a fairly good championship bonus,” he said in an interview he gave for the Royal Automobile Club Talk Show in conjunction with Motor Sport Magazine in 2019.

“So I at least expected to be earning what I’d been earning the previous three years. I was a bit upset about it in truth, I felt I was being taken advantage of.”

Newey said he never understood this offer. He speculated in his book: “Perhaps it was Ron trying to be clever, thinking I had no alternatives. Or maybe he was punishing me for not swearing undying allegiance” back in 2000.

Enter Bobby Rahal - then Jaguar F1 team boss. Newey had been his IndyCar race engineer in the 1980s, and Rahal had tried to get him involved in multiple IndyCar projects - including the aborted Ferrari programme - since then.

By chance Rahal called Newey around the time of McLaren’s offer of a pay cut. They met up, and discussed Jaguar’s ambitions, finances and resources. Then Rahal offered Newey two and a half times as much as his original McLaren salary to make the move. Newey described the number as “almost unbelievably big”.

He also liked the fact it was a flat rate with no bonuses, as he was still smarting from the fact that Mercedes engine failures he could do nothing about had cost him a world championship bonus with McLaren in 2000.

Despite being unsettled by meetings with Niki Lauda - then in a senior Ford role - things progressed to the point where Newey committed to telling Dennis he was leaving for Jaguar.

Newey said: “Ron rubbished Jaguar's aspirations, warned me of a power struggle between Niki and Bobby, asked if I wanted to end up working for Niki, which is what would happen if Niki won that particular power struggle.”

Newey called this a “masterstroke” from Ron, because he was only interested in going to work for Rahal, and he didn’t want to “become a pawn in a Ford management-backed power struggle within the team”.

Dennis also matched Jaguar’s financial offer, and promised Newey he would have the freedom to explore projects outside of F1, such as the America’s Cup sailing competition.

Ultimately Newey felt the Jaguar move was too big a career risk, so after leaving the room to discuss it with his wife, he went back to Ron and agreed to stay.

A famous F1 farce followed as Jaguar went ahead and announced Newey was joining anyway, McLaren responded with its own announcement on the same day that Newey was staying and eventually an “amicable resolution” was reached for him to stay put, made possible legally because he had only signed a letter of intent with Jaguar. Dennis also turned out to be right about what would’ve happened at Jaguar, with Rahal soon ousted and Lauda in sole charge of the shortlived team.

But though Newey stayed in 2001, the repercussions set up his eventual McLaren exit four years later for the Red Bull team that Jaguar had by then become.

Newey’s attempt to leave led to McLaren creating the infamous “matrix management structure” in a bid to prevent the team ever being so vulnerable to the departure of one person again.

“Ron kept me, but he didn’t like it. I suspect he didn’t like the fact that one of his employees had become close to being indispensable and had, in his eyes, held him to ransom,” Newey wrote. “Unbeknown to me, he charged Martin Whitmarsh with ensuring that this could never happen again.”

So Newey became entwined in a structure with various department heads and ‘performance creators’. He declared that the new system “didn’t work”, and he described it in his book as “not an environment in which I flourished”. He also said the structural changes led to the 2002 McLaren being “a clumsy design - certainly not one of my best”.

A further nail in the coffin of the McLaren relationship followed during the debacle over the unraced 2003 MP4-18 design. Whitmarsh led a group arguing that with reliability improvements it could be the basis of the 2004 car. Newey was adamant a new monocoque was required to solve the stability issues it had. A vote of engineering heads was called, and Newey’s faction lost.

“I have to admit I totally lost it, called Martin all the name under the sun and stormed out - not my proudest moment,” Newey wrote.

“Not only did I feel strongly it was the wrong decision, but also my opinion had been squashed by committee - effectively I was no longer technical director.”

After a very poor start to 2004 with the rebadged car, Newey eventually got his way - and the new chassis version was competitive enough to win the Belgian GP.

All of which was firmly in Newey’s head going into 2005, Red Bull’s debut F1 season. Its team boss Christian Horner was aware Newey was far from happy at McLaren, and embarked on a months-long wooing process that advisor Helmut Marko and now Red Bull driver Coulthard joined.

The deal was eventually announced in early November, by which time Newey had already been marched off the premises at McLaren as soon as he’d told Dennis the news.

Newey said in his book that one of the big things that appealed to him about Red Bull was the chance to be with a team from almost the beginning. He said it felt like unfinished business from his time at Leyton House, where the rug was pulled from under the team just as things were coming together.

For Red Bull, Newey joining changed everything.

As Horner put it on the firm’s Talking Bull podcast: “Having Adrian join the team was the turning point that we went from being the party team to ‘These guys are serious’.”